Jesuit Transmission

The Qing dynasty began in the middle of the 17th century with the Manchu Conquest from the north. Its Golden Age began with Emperor Kangxi, who ruled from 1661 to 1722, and continued through his son, Yongzheng (1722-1735), and his grandson, Qianlong (1735-1796). During this period of territorial expansion, the Qing furthered the integration of polity and culture. Imperial power was retained through ritual, ceremony, authority, militarism, and civil administration.

|

|

|

| Adoration of the MagiJerome NadalAntwerp, 1596(more) |  |

Portraits of Emperor Qianlong,the Empress, and Eleven Imperial ConsortsQing Dynasty, 1736(more) |

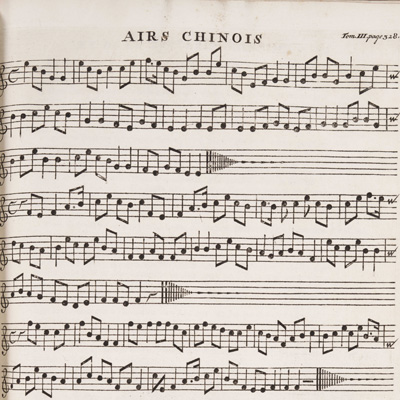

The Jesuits, including Jean-Joseph Marie Amiot, were allowed to stay in Beijing under strict supervision of the Imperial household. The Qing wanted to learn from the Jesuits about western sciences and technology: mathematics, cartography, and astronomy and their application to practical military concerns like weaponry, scientific instruments, and mapmaking. Simultaneously, the Jesuits were exposed to the music at the imperial court. The qin, an instrument associated with the music of scholar-officials, is shown in Amiot’s Memoire and under "Music in China."

|

|

|

|

|

| China IllustrataAthanasius KircherAmsterdam, 1667(more) |  |

Memoire sur la Musique des ChinoisJean-Joseph Marie AmiotParis, 1779(more) |  |

General History of ChinaJean-Baptiste du HaldeLondon, 1741(more) |

Early European understandings of China relied heavily on Jesuit accounts and organized compilations of these accounts in books like Athanasius Kircher’s China illustrata (1667) and Jean-Baptiste du Halde’s Description de la Chine (1735). The prevalent western image of China at that time was one of a deeply moral and cultured nation which practiced a form of monotheism similar to Judeo-Christianity. The Jesuits sought to link China with a biblical past, as a colony peopled by the offspring of Noah’s son Ham, while Enlightenment philosophers, including Voltaire, saw in China a moral, intelligent, and well-governed society that was not Christian. Either way, European society was intensely sympathetic toward China during this time.

|

|

|

|

|

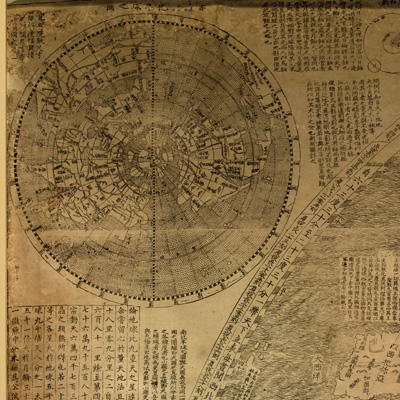

| Mappa MundiShanghai, 1921 (facs)(more) |  |

Transcriptions of Chinese Melodiesfrom General History of ChinaJean-Baptiste du HaldeLondon, 1741(more) |  |

Les CyclopesJean-Phillipe RameauParis, 1729-30(more) |